Workshops on fundamental human rights in times of COVID-19

Every person in the world has basic rights – regardless of race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. This was concluded in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights: in 1948, signed by more than 190 states to date. However, human rights have been and continue to be violated all around the world by companies, governments, groups and individuals. Global movements are advocating persistently for a rightful implementation, especially in the times of COVID-19. During the pandemic, which created a fertile ground for different kinds of human rights violations and increased the difficulty of intervening due to lockdowns, they have found particularly creative solutions to keep on campaigning for human rights.

Daniela Schier and her team of human rights educators for Amnesty International in Austria are moving workshops to the Internet – and have already found engaging tools and methods to do so. In this interview with our author, Clara Maier, she illustrates why human rights education is especially important in times of COVID-19, how emotions can be conveyed online, and further reveals the challenges posed by data protection guidelines.

Why is it especially important to teach human rights in the time of COVID-19?

In difficult times – and that is how I would describe the last few months – it is once again important to strengthen people in terms of human rights. Especially when they themselves are reaching their limits and are longing for stability and support. Crises make already existing grievances more visible and often reinforce them. People living on the margins of society are often hit the hardest. We are convinced that working with human rights strengthens people because they recognize the power that lies within them. Our approach is that dealing with human rights is something lively and fun. That is why we find it important to continue with our workshops. Another thing is that we want to use this small door that has opened up with online education as an opportunity – and to see if it is possible to give a certain positive input in terms of human rights online as well.

Does it make a difference that, in the time of COVID-19, human rights affect us on a more personal level?

During the pandemic, we are experiencing firsthand that our basic and human rights are being restricted. When that happens, we can either fall into a faint and become incapable of action, or we can strengthen ourselves by recognizing that our human rights are being restricted and that it is necessary to point this out – and to do something about it. We talk about empowerment here. Our ultimate motive in our workshops is that we want to make human rights tangible. In doing so, we have a positive approach and want to get people into action – with the goal of standing up for their own rights and the rights of others. Human rights must be protected and preserved. We must all stand up for this.

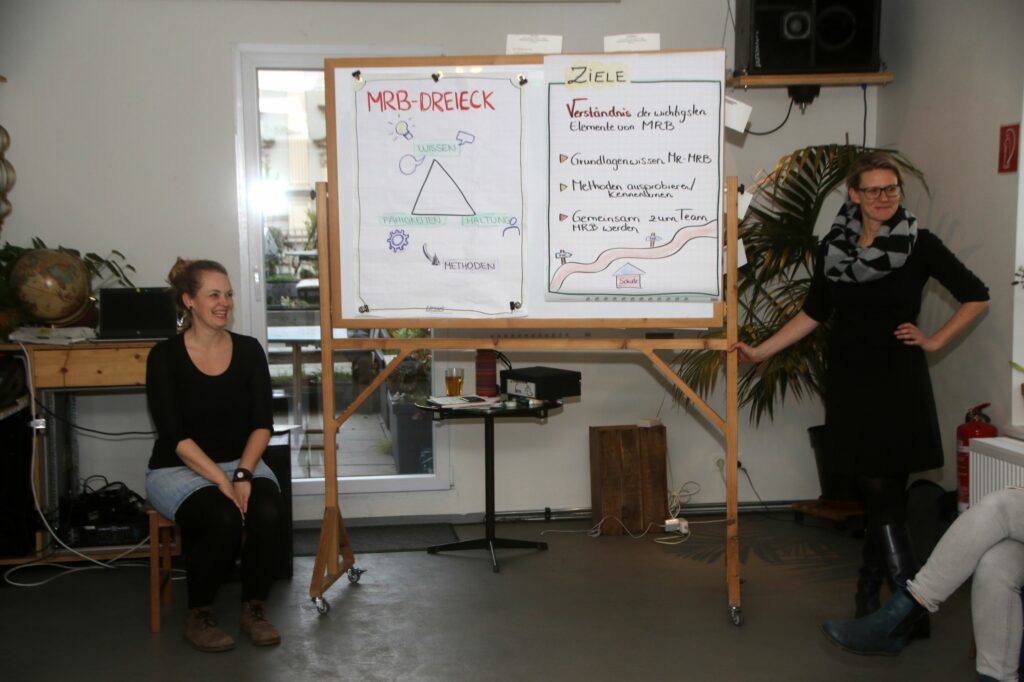

You work with an educational triangle: knowledge, skills and attitude. These aspects are taught in the workshops, does that work online as well?

People often think that only knowledge can be shared online. You show slides, go through them quickly, and that’s it on the mental and factual level. But in our workshops, we see very clearly that we can also reach people very well on an emotional level and address their attitudes. We saw this, for example, in an online exercise where participants had to close their eyes to put themselves in the shoes of a victim of police violence in Chile. Gustavo Gatica, a young psychology student, was blinded forever in 2019 when security forces fired rubber and metal bullets at people during a protest. In the exercise, the participants were truly overwhelmed. If you guide the methods online appropriately, the emotional level can also be addressed very well. I think that is perhaps the secret of our success.

In schools, the transition to online instruction is often difficult. Why is Amnesty (more) successful with this?

That is hard to say across the board. Some teachers have told us that they have always worked partly online and that during the lockdowns, the students are even more efficient than before. Then, of course, there are also people who find it difficult and do not want to deal with new methods. These are then their own hurdles, which they carry into the classroom. I think the spectrum is very wide and depends on the teacher on the one hand, and on the students and their access to computers, the internet, and a quiet workplace on the other. We also have to remember that we come into the classes as “outsiders.” That is usually a starting advantage. In addition, our workshops are very interactive – also online – and we ask for the students’ opinions. It sounds banal, but unfortunately that is not ordinary.

You have designed the workshops very quickly. The training of the trainers took place in October already. Where did the know-how come from and how did you approach it?

Our advantage was that we could approach the topic from three different perspectives: first, we have trained teachers in our team. Second, we already had a taste of e-learning in adult education last year and gathered expertise. Third, we simply tried things out and saw what worked. We set up the workshops, tried them out ourselves, then went into classes and asked quite openly: We would like to try this out, are you ready to join us and tell us how you experienced it afterwards? We found classes that provided great feedback and noted what we could still improve. Other things, like the Kahoot quiz (note: a popular, quick to use online learning quiz), have been well received from the start.

And how was the motivation in your team?

Surprisingly, many of us developed a real passion for online education. We started to think: Hey, this is actually really cool! This attitude got us immersed in the topics. When we realized it was working and got positive feedback, that became the driving force.

In a development process some ideas always fall by the wayside. What ideas did you have to say goodbye to?

The wave of digitalization came at the same time as the wave of data protection, which is something that tends to limit our possibilities. The passion I mentioned earlier has led us to find a lot of cool tools, but they are not always compliant with data protection laws. In the coming months, our challenge will be to find alternatives that are ok from a data protection perspective – because of course we want to play where the cool kids play!

Will the online workshops continue after the lockdown?

Yes, we definitely have to continue. The winning argument is, of course, that the online format makes us supraregional: Trainers who are based in Innsbruck in West Austria can, for example, do a workshop in Mühlviertel in the East, more than 300 kilometers away. I find that alone very exciting. The next considerations are to make the workshops hybrid. For example, you could hold a face-to-face workshop and then hold other workshops online, so that sustainability is given and the students can deal with the topic for longer.

Finally, what are your recommendations for online workshops?

Keep the passion for your topic and bring along a good amount of patience. When you do things for the first or second time, it can take a few tries. Of course, good preparation makes a lot of things easier, but at the same time, technology, for example, does not always play along. That is where composure is very important. You should also understand the tools and try them out from the student’s point of view. Otherwise, it is all about feeling comfortable with the methods and doing something that excites yourself. Apart from that, of course, a good Internet connection, a serious background, and no pajama bottoms. (laughs)

The interview was conducted in German and translated into English.

Other initiatives in Austria

In Austria, various organizations – from nationwide movements to small local communities –are committed to good coexistence, a diverse society, openness, and human dignity. Just like the list of human rights violations, the list of initiatives that engage for the respect of human rights is quite long as well.

In Graz, for example, the non-governmental organization Zebra had to interrupt personal counseling and therapy during the lockdowns. They set up a “Sorgenhotline” (crisis line) with interpreters to keep their activities going. Well understandable information has been translated in different languages. Going online is considered important by many movements, such as YoungCaritas in Vienna. In December 2020, they initiated a Zoom-Livetalk about the situation of homeless people in winter. A social worker talked about experiences on the street and answered questions. The film festival “This human world”, also based in Vienna, moved their screenings and discussions about social political challenges, human rights and freedoms to the digital sphere. A festival pass allowed admission to four or five virtual cinema halls per day with films, directors statements, and discussions included.

In Innsbruck, the association “Miteinander am Berg” had to severely limit its inclusive climbing activities that have been uniting Austrians and refugees, but also shifted them – as best as possible – to the Internet. Online workout trainings have been held regularly until climbing outdoors or in the climbing hall is possible again. In addition, telephone exchange with the participants ensures that they keep in touch and support each other. SOS-Menschenrechte in Linz usually offers workshops. In Covid times, they instead constructed virtual tours of the House of Human Rights and webinars on various human rights topics including a quiz.